Learn about the complex mahi behind Operation Nest Egg, the nationwide kiwi recovery tool established in 1995

How does Operation Nest Egg work?

Monitoring breeding pairs

The first step in Operation Nest Egg is the most time-consuming. In fact, finding and monitoring breeding pairs of kiwi takes up 50% of Operation Nest Egg’s overall effort and resources.

Pairs of kiwi are located and transmitters attached to one or both parents to determine when they are nesting. With Brown kiwi, only the males are monitored because they do all the incubating. When their behaviour changes it indicates they are sitting on an egg. With other kiwi taxa, males and females share incubation.

Collecting eggs or chicks

Choosing the optimal time to remove an egg is vital. Too soon, and the egg could fail. Not only that, more human resources are required to keep it alive, warm, and well in a captive rearing facility. Too late, though, and the egg may succumb to predators or adverse weather, or may have hatched on its own which means its parents are less likely to lay another clutch that season.

The aim is to collect eggs that are at least 25 days old. If they’re less than 10 days old, there is only a 1% chance of hatching success. If they’re 10-20 days old, the likelihood of success reaches 20%. If the egg is 30 days old, success increases to 75%. By 70 days, the chance of hatching a chick reaches 90%.

Clever technology is helping kiwi workers get the timing just right. One, known as the Egg Timer™, electronically monitors breeding adult birds. When their movement patterns change, it’s clear that they have begun incubating the egg and kiwi workers can then calculate the best time to collect it. This saves hours of time that used to be spent keeping track of breeding pairs.

The Egg Timer’s™ successor is the Chick Timer™. This helps field workers pick up newly hatched wild chicks rather than eggs. This is a good option if there is a risk that an adult bird, when disturbed, could stomp on and break the egg. It is also useful if the burrows are too deep to successfully retrieve the egg, such as with roroa/Great Spotted Kiwi and rowi.

Transporting eggs or chicks to captive rearing facilities

Once kiwi eggs or young chicks have been collected from nests in the wild, they are transferred to captive rearing facilities.

If an egg is being transported, special containers are used to keep it secure and warm. Newly hatched chicks are also carried in special boxes, but if an older chick is being moved, it goes into a carry box similar to the ones used for adult kiwi.

The aim is to get the precious cargo to a captive rearing facility as soon as possible. 12 hours away from the nest is the maximum time limit for an egg. Chicks can be on the road for a little longer. While it is important to keep them warm, it’s not necessary to feed them as they live off their retained yolk for the first 5-7 days.

Captive rearing

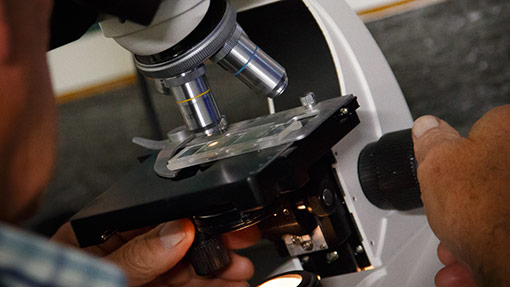

When an egg arrives at a captive rearing facility, it is ‘candled’. This is a technique that uses bright light to reveal what’s inside. It shows whether the egg is alive and what stage of development the embryo has reached.

The success rate for hatching kiwi eggs in captivity is 80-90%, and about 65% of chicks survive to adulthood on average.

Whether they arrive as eggs or hatched chicks, the young birds are kept in a predator-free environment until they’re considered ‘stoat proof’ and could comfortably fend for themselves should they meet a stoat in the wild.

Photo credit: Jenny Feaver

Kiwi crèches

A kiwi crèche is either an island or an area of land with a special fence built around it to keep predators out. All predators are also removed from within the fence, creating a safe haven for kiwi.

When kiwi chicks are about two weeks old, they are moved from the pens in the captive facility to a crèche until they reach a weight at which they can better defend themselves against the paws and jaws of predators.

It is important to get the chicks into crèches as soon as possible, away from both the risk of disease and people. The young birds need to learn how to be a kiwi and fend for themselves, and not get too used to having people around. Using crèches also helps cut down the costs of Operation Nest Egg as they are less expensive to run than captive rearing facilities.

Crèches have been set up in both the North and South Islands, each one dedicated to just one kiwi species and most of them on islands. Many have been funded and set up by community groups.

Photo credit: Jenny Feaver

Release back into the wild

When young birds reach about 1kg in weight, they are better able to defend themselves against stoats. This is when they can be safely returned to their wild home, or transferred to a new site to establish a new population. Local iwi often farewell and/or greet the young kiwi with a welcoming ceremony.

If the birds are going to an established site, they are simply released. If they are part of a new population, then transmitters are attached so their welfare can be monitored.

If the chick stayed on-site at the hatching and rearing facility, it has to go through a disease-screening quarantine period to make sure it is fit and well and will cope with living in the wild. These young birds will sometimes have a transmitter attached to their leg so that their movement can be monitored once released.

Photo credit: Jenny Feaver

Advocacy

We’re all in this together. Save the Kiwi works to raise awareness about the plight of the kiwi and what is being done to help via social media, regular newsletters, and media publicity. (Photo credit: Jenny Feaver)

Predator control

Stoats, ferrets, rats, dogs, and other predators are the greatest risk to the kiwi population. Find out more about predators, the harm they cause to our native taonga, and what we can do to help.

Kiwi avoidance training

Dogs are the biggest threat to adult kiwi. Learn about a method that can successfully teach dogs how to avoid kiwi when they come across them in the wild.

Operation Nest Egg

Operation Nest Egg is a national kiwi breeding programme which grows kiwi numbers much faster than they could in the wild. Find out more about what and who is involved. (Photo credit: Jenny Feaver)

Kōhanga Kiwi

Kōhanga Kiwi is a ground-breaking strategy that both preserves current numbers of kiwi and increases them. Learn about this world-leading conservation initiative.

Gallagher Kiwi Burrow

The Gallagher Kiwi Burrow (formerly known as the Crombie Lockwood Kiwi Burrow) is Save the Kiwi’s kiwi incubation, hatching, and brooding facility. Learn about the facility and the chicks that temporarily call this facility home.

Whānau, hapū, iwi & kiwi

Kaitiakitanga is integral to the spiritual, cultural, and social life of tangata whenua. Find out how Save the Kiwi is committed to supporting Māori leadership in kiwi and wider efforts to restore the health of the whenua.

Jobs for Nature

In 2020, Save the Kiwi was awarded Jobs for Nature funding which was redistributed to various kiwi conservation projects. Find out about these projects and the environmental gains they’re seeing. (Photo credit: Jenny Feaver)

Research

An enormous amount of research about the kiwi population has been undertaken over the years. Learn about the research behind Save the Kiwi’s vision.